A Journal of the Broken Screen

Robert Smithson, Towards the Development of a "Cinema Cavern" (1971) Pencil, photography, tape. 12 5/8" x 15 5/8".

Robert Smithson, Towards the Development of a "Cinema Cavern" (1971) Pencil, photography, tape. 12 5/8" x 15 5/8".The current issue of Cabinet magazine has the theme of "underground" and the usual diverse mix of subjects includes a short essay by Colby Chamberlain on Robert Smithson's proposal for an underground cinema, outlined in his 1971 Artforum essay "A Cinematic Atopia" and also in a drawing - reproduced in cabinet, also from 1971 - with the handwritten title: Towards the Development of a Cinema Cavern or the movie goer as spelunker.

Smithson's drawings reveal the basic architecture of his scheme: " The projection booth would be made out of crude timbers, the screen carved out of a rock wall and painted white, the seats could be boulders. It would be a truly "underground" cinema." (The Collected Writings, 142).

Chamberlain's article focusses on Smithson's use of the word "underground." If Smithson was most directly referencing the underground cinema of Stan Brakhage, Ken Jacobs, Robert Breer and others - and its accompanying organizations such as the Film-Makers Co-op - Chamberlain highlights how in 1971 the word had already become a global cultural phenomenon, with the underground covered extensively in Time, Newsweek and Life. Chamberlain also highlights how the term has a broader cinematic usage as well - first used by Manny Farber in 1957 to praise the works of Howard Hawks, Val Lewton and other directors of 1930's and 1940's action movies.

Such a complex of origins, uses, and etymologies also characterize the cinematic experience as it appears in Smithson's essay. Beginning with a phenomenological account of cinema going, Smithson focusses on the "immobilization of the body" that causes memory to become " a wilderness of elsewheres." Instead of writing about film, Smithson focusses on how the elsewhere's of all the films he has seen "reconstruct themselves as a tangled mass," an ever canceling void where abstract films are countered by Hollywood movies whose stories and characters are "enough to put one into a permanent coma." So Smithson imagines a film encyclopedia but there, too, "Categories would destroy themselves, no law or plan would hold itself together for very long."

The Cavern Cinema, then, emerges as the redemption of this situation, as a cinema which, by virtue of its isolated location and by only showing the film of its own construction, returns a definitiveness to the cinematic experience. And yet, the cavern cinema is also not an alternative to but an ultimate realization of the limbo, void, and coma characterizing the cinema experience:

The ultimate film-goer would be a captive of sloth. Sitting constantly in a movie house, among the flickering shadows, his perception would take on a kind of sluggishness. He would be the hermit dwelling among the elsewheres, forgoing the salvation of reality. Films would follow films, until the action of each one would drown in a vast reservoir of pure perception.

He would not be able to distinguish between good or bad films, all would be swallowed up into an endless blur. He would not be watching films, but rather experiencing blurs of many shades. Between blurs he might even fall asleep, but that wouldn't matter. Soundtracks would hum through the torpor. Words would drop through this languor like so many lead weights.

This dozing consciousness would bring about a tepid abstraction. It would increase the gravity of perception. Like a tortoise crawling over a desert, his eyes would crawl across the screen. All films would be brought into equilibrium - a vast mud field of images forever motionless. (141-142)

Flam's edition of Smithson's Collected Writings presents A Cinematic Atopia alongside images of Smithsons film of A Spiral Jetty, in a manner redolent of Smithson's own image-text magazine essays. It suggests a reading of all of Smithson's work as in some sense cinematic, that part of his dialectics of landscape was a search in remote places for a kind of cinema, an image factory where the true cavern cinema could be built, mocking a cultures productivity but also embodying it, distilling as well as expanding experience and meaning. The simultaneous life and death, reality and illusion of the cinema is a revelation of Smithson's entropic world view.

I'm trying to imagine the cavern cinema and the effect and meaning of its materials, spaces and experiences. In the cavern cinema stone, wood and projected images present a spectrum from permanence to intangibility, yet within the cinema each partakes of some of the qualities of the others: looped film on stone gives the later some of the intangibility, movement and shadow play of the former. Perhaps wood is preserved in this underground bunker. Certainly, it moves closer towards the monolithic, permanent quality of stone. Images are given something of the definiteness of matter by having an immediate correlation with their environment.

It's an intoxicating mix, but, of course, it's one that even as it enjoys the fantasy of perpetual motion, is ever prone to break down and collapse. As elsewhere in Smithson's work, the cavern cinema is deeply entwined with notions of decay and entropy. Smithson's essay concludes with a list of the field trips that have comprised his search for a location for the cavern cinema, to caves, mines and quarries in Vancouver, New York State and California, but it's noticeable that each ends in failure - or, in Smithson's entropic riddled language: "the project dissolved", "nothing was done." Attempting to realize the cavern cinema Smithson encounters in these subterranean vaults the fantasy and impossibility of the cinematic image.

The 1957 "Classics Illustrated" comic book edition of Jules Verne's A Journey to the Center of the Earth, reprinted from Cabinet 30.

The 1957 "Classics Illustrated" comic book edition of Jules Verne's A Journey to the Center of the Earth, reprinted from Cabinet 30.

Given it was never built, photo documentation of the cavern cinema is limited. There is one photo, originally from Sports Illustrated, that Smithson taped on to his schematic plan. It shows the humorous theatricality with which Smithson conceived his proposal: a spelunker heading up a cave, the light on his head - like the light from the cinema projector - lighting the cave in front of him. Smithson's use of this photo activates the debate around performance of his unpublished 1967 essay From Ivan the Terrible to Roger Corman or Paradoxes of Conduct in Mannerism as Reflected in the Cinema. The ultimate effect is not dissimilar to what Smithson says there of Warhol's films: "the phony naturalism of we're-just-ordinary-guys-doing-our-thing becomes brilliant manneristic travesty." (349) This, too, is a dynamic of the cavern cinema.

Smithson and Warhol are certainly both artists with a complex relationship to notions of "underground cinema", a fact noted by Saul Anton's recent novel Warhol's Dream (2007). As I begin to think how to develop a relationship to Smithson's cavern cinema, treating it as a continuing process rather than an concept in drawing and essay, I'm drawn to the imagined conversation of Anton's novel for the way ideas are exchanged between Warhol and Smithson in continually refracting patterns of similarity and difference, sympathy and incomprehension, admiration and annoyance:

BOB I once thought about making a piece called Underground Cinema. It would be a theater but the only film it would show would be one of is own construction, how it was dug and hollowed out of the ground. Instead of a camera seeing itself, it would be a space spacing itself, a document of its own future. The moment the cave was complete would also be the end of the film.

ANDY That sounds fascinating. Did you ever make it?

BOB It's an impossible proposition. The subject of the film, the cave, only comes to be after the film is finished. It means that the film is filming what is in fact a future that hasn't arrived yet, and which arrives at precisely the moment it stops recording. When you can finally see the film, you're seeing a past that doesn't belong to the present.

ANDY I think that's what love is like. You're working toward it thinking you're about to get there, but by the time you do, you're already trying to recapture it because you think it's gone and you want to get it back. That's how it always is on soap operas. (139-40)

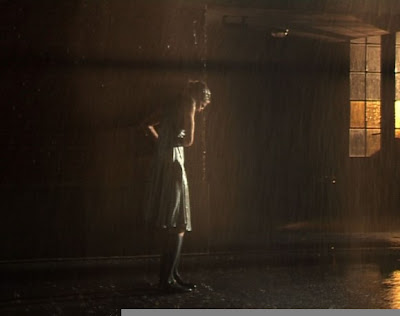

Top: Chantal Akerman, To Walk Next to One's Shoelaces in an Empty Fridge (2004). Middle and bottom: Women from Antwerp in November (Femmes d'Anvers en Novembre) ( 2007). All images copyright the artist. Courtesy Marian Goodman Gallery, New York/Paris.

Top: Chantal Akerman, To Walk Next to One's Shoelaces in an Empty Fridge (2004). Middle and bottom: Women from Antwerp in November (Femmes d'Anvers en Novembre) ( 2007). All images copyright the artist. Courtesy Marian Goodman Gallery, New York/Paris.

What do we learn from the Chantal Akerman show at the Camden Arts Centre? First, this is an artist who wants to explore the image in space, where it becomes multiple, both in its own patterns of projection and through the movements of its audience. Second, this is an artist for whom the film image is always entwined, overlaid, is itself language. Thirdly, this is an artist acutely aware of film style and its consequences, making decisions about form and media, fully aware of how each constructs self-hood and society in unique ways.

The first part of To Walk Next to One's Shoelaces in an Empty Fridge (2004) comprises a large gallery-filling spiral tulle. On the tulle are projected lines of text, accompanied by quiet, classical music. I couldn't read much of the French text or identify the music, but the piece is a meditative experience, through which the viewer can wander, choosing their position in regards to shifting tides of words, with both sides of the tulle screens, lights and shadows, having equal value. A translation would have been useful, although the work has its own phenomenological completeness without it. It's also usefully viewed holding in mind Edna Moshenson's summary:

It is a cinematic autobiography of sorts, which contains her thoughts about cinema and the power of the cinematic image; about the Second Commandment that forbids that making of graven images; about her work and about what has nourished and motivated her. Other parts of the text touch upon her family biography - her relations with her mother and the experience of growing up and living in the shadow of trauma, silence, nightmares, and invented memories. (Chantal Akerman, A Spiral Autobiography, 16)

The second part of To Walk comprises another tulle screen hanging in the middle of the gallery, and on which are projected pages of handwriting and a portrait from an old notebook. On the wall of the space a black and white double screen film documents Akerman and her mother discussing Chantal's upbringing, her mother's experience of the concentration camps, and, principally, the notebook, which belonged to Chantal's grandmother, who died in the camps. Depending on where you stand to view, the notebook on the tulle can be visible or absent, foreground or background, but it is always part of the experience.

Ackerman asks her mother to read from the notebook. The film documents her struggles, both to make sense of the handwriting and to remember her Polish reading skills. The notebook begins "I am a woman! That is why I cannot speak all my desires and thoughts out loud..." - and Akerman has to point out the message to her mother, making sure its presence becomes acknowledged. Even here, amongst intimacy, family and friendship, possibilities of silence and mis-representation are always present. Such histories are also tied to Akerman's development as a film-maker, informing her mothers conviction she should follow her passions, whilst her father was more cautious. Chantal observes that only in her first film - the short Blow Up My Town (1968) - has she ever been able to combine the tragic and the comic that defines her families experiences.

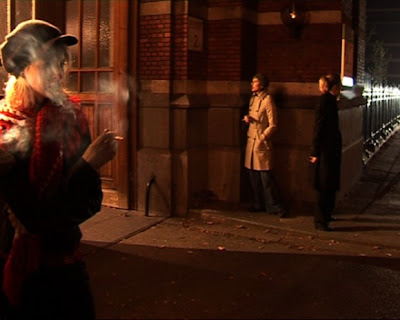

Both images: Women from Antwerp in November (Femmes d'Anvers en Novembre) (2007). Copyright the artist. Courtesy Marian Goodman gallery, New York/Paris.

Femmes d'Anvers en Novembre (Women from Antwerp in November) (2007), the show's final piece, is where we see Ackerman's awareness of style and film genre most at work. On one side of the gallery is a five screen production of young women smoking. The shots and the women differ but they are all heavily stylised in a way evocative of film noir and advertisements. Women smoke whilst on the phone, alone in moodily lit alleyways, in black and white, in the rain. There are other images which disrupt this a little bit - notably one of the women gathered around a table - but they too become part of this analysis of a social act - one made popular through its visual stylisation, not least in the history of cinema, which is here also linked to certain categorizations of femininity. The installation recalls Akerman's 1979 comment on her work:

I try to make a very distilled cinema where there are no images that are, let's say, sensational. For example, instead of showing a 'public' event because it is sensational... I will tell the story of something small nearby.

Here that "distilled cinema" means taking on directly a particular form of cinematic representation, inhabiting it, beginning to subjectivise it. As well as smoking's now problematic status, this is explored through a second screen in which one of the women is filmed in what looks like HD video close up: the camera lingering over mouth, lips and face as she smokes a cigarette. Still stylised, of course, but not so it can be designated as glamorous according to the codes of film noir. It is not possible to watch both screens at once, the end result being a piece and viewing experience that proposes a contemporary subjectivity combining spectacle, film style, femininity, sense of self, private and public modes of being.

The show also includes Akerman's 1972 film Hotel Monterey. Over 65 silent minutes, Hotel Monterey is constructed as a series of spaces - corridors, rooms, beds, lifts, doorways - that in long, meticulously framed shots become negotiations between spaces, light, movement and the people that sometimes come into them. Camera movements comprise slow pans along rooftop railings or a long, slow zoom up and back along a corridor to a whited out, over exposed window. The film stock suggests a building being subsumed in a psychologically charged heaviness of murky greens, browns, blue and yellows. Outside shots are are always related to the inside: skylines are outer manifestations of a buildings heating and water systems.

Documentation and abstraction, neutral observation and obsession, the new and the haunted, the framed and random, time changing, time frozen. Here is Akermans film career beginning, bearing testimony to the alien and familiar experience of America, and also the cinema of Mekas, Warhol and Snow she encountered there. In making work for galleries, Akerman often re-works or combines films to create multi-screen installations. Here the act of looping a film with no credits or title sequences is all that is required to link the films temporality to the patterns of memory, history, trauma and representation that the show's more recent pieces explore, perhaps more consciously.

What do we learn from Akerman's exhibition at the Camden Arts Centre? I started with this question because each of the pieces here approach a specific problem, seeking to learn something about it, at the same time as recognizing what they want to learn, its connection to history and trauma, is perhaps unknowable, only revealable in traces of "something small nearby" to which Akerman is so attuned. The artists only approximation of certainty is in the works form. Often, too, there is the hope that the image itself could be a form of writing. In a world dominated by availability of cinematic images, the written language in these pieces proposes a system of representation that requires debate, translation, embodiment, relationship, distance and layering to begin to, tentatively and hopefully, become legible.

Retrospectives are a difficult format for certain varieties of contemporary artist. If your work is engaged with moment, site, and process then is it compatiable or even possible to have a traditional gathering of all your work together, in one institution at one time? And what role should the accompanying catalogue play? For his retrospective at the Musee d'Art moderne de la ville in Paris, Philippe Pareno came up with one solution. Whilst the exhibition was used as a site for current work, it was the catalogue, Alien Affection, which served the function of a chronological retrospective, as if in book form the combination of documentation and contemporaneity was possible.

Gonzalez-Foerster has collaborated with Pareno, and also had an exhibition at the same institution, but, until recently, catching examples of her work at different shows in London - including Tate Modern's The World as Stage and recent series of experimental French cinema - I'd not found a publication that fulfilled the function of Alien Affection, giving an over view of her work at the same time as discovering the distinct identity it could take when thoughtfully presented in book form.

Thankfully, Nocturma*, the exquisite catalogue for her show at MUSAC, Leon, Spain (17th May- 7 September 2008) has now fulfilled that role. Although a concluding "pictorama" of thumbnail prints concludes the book with a survey of her work from 1977 to the present, the book is less a retrospective than Alien Affection. Perhaps indicating the difference in their respective practices, and the kind of responses they illicit, Nocturama* is best read as an exploration of traces, what lingers, as an exposition upon the after-image of an art practice.

Nocturama, that is, with a "*." Whilst such a symbol might normally be used to limit and frame the claims of a statement, here the accompanying back page note offers a coda for the work and also for the sense of the book form, expanding into suggestiveness, specificity and neologism as a form of world making:

*and books, cinecity, cosmodrome, exotourism, expodrome, park, promenade, solarium, tropicalization...

Three essays highlight different aspects of DGF's work - again less interested in chronologies of DGF's career than in isolating a particular effect and moving around within that quality. So Ina Blom explores the idea of spectacle as derived from Debord, observing that DGF embraces spectacle but also finds in it a place for individual consciousness and bodily experience, drawing connections to, amongst others, Helio Oiticica's film and space explorations:

To enter the cinematic world of Gonzalez-Foerster is therefore above all to be invited to trace the open-ended temporal meandering or ambulation of a form [of] human existence that seems to be defined at the level of pure sensation - yet a form of sensation that is continually confused with the working of media machineries, with the ticking of the video time code, the deft segueing of one image into another, the dumb, staring, stillness of the camera. A story of the mind-machine, in other words: it might sound like a paranoid scenario, a meeting of old-school sci-fi imagination and radical media critique. The result, however, is less easily definable. For the main achievement of this work is precisely its ability to explore the surprising range and scope of this type of existence. In fact, the more it closes in on the idiosyncratic details of technical frameworks, the more it seems to bring out the type of open-ended, uncontrollable, non-formatted moments that might actually be the key product of this mediatic 'life of the senses.' (66-67)

A three way dialogue with Hans Ulrich Obrist and the novelist Enrique Vila-Matas is focussed largely around the opinions and work of Vila-Matas. The talk serves to illustrate the immersion of DGF's recent work in a certain canon of written literature that moves from Kafka, Borges and Robert Walser through to Bioy Cesares, Philip K.Dick - particularly the early books such as The Broken Bubble - Robbe-Grillet and Julien Gracq. As an installation shot reveals, DGF even places a wall text at the entrance to a video installation which reads:

having been a prisoner of literature for two years or more, captured in a triangle of enrique vila-matas, roberto bolano and w.g.sebald, three children of robert walser and j.l.borges, it is impossible for me to prsent anything else here than three short stories which can be seen or read in any order.

The dialogue extends to the careful construction of this catalogue, as too it includes the creation of spaces for reading, and bookcases made of books, both works documented here. As, also, in a brief interview in the current issue of 032c magazine, DGF observes:

Places and contexts can be very different, but my approach remains similar in all cases: simply read books and walk around, or walk around and read books. Some places are more urban, some are intense, some have a great void, but there is always a potential narrative. A writer like W.G.Sebald is an interesting archtetype for the way many visual artists deal with cities, places, documents, memories and cultures. (30)

This Sebald template can often lead to a sense of history bordering on nostalgia, as in Tacita Deans portrait of Michael Hamburger, shown last year at London's Frith Street galllery - whereas for DGF it feeds into an obssession with hyper modern spaces. Not that there isn't a romantic quality to her own work, and the environments to which she is attracted. Blom, again, highlights this, stressing DGF's use of lamps, a romantic trope associated "with both mental projection and spatial creation" referencing both the artificially lit city and the workings of cinema projection.

The final contribution, by Penelope Curtis, in its own form places storytelling alongside critical thought - storytelling as critical thought - seeing this as the appropriate response to the suggestiveness of DGF's work, responding in kind to its invitation, with a combination of viewer and critic. In an astute commentary also of use in thinking through the role of the book in this kind of art practice, Curtis discusses DGF's miniaturized sculpture park and the effects of scale:

reduced scale-replica's of previous exhibits were assembled all together on one of the city's lawns. Like memories - as much right as wrong - which have faded a little with time, and in which things now no longer have their originally allotted site, but are re-assembled in the single space of our conscious, the sculptures all become a little more like each other, while retaining their essential difference. Now they are primarily a collection of sculptures - like a collection of glasses, or of egg-cups - which may vary individually, but which all still fall into the category of sculpture. (102)

This produces a crisis of meaning which again seems apposite to the process whereby art works are reproduced in bookworks such as Nocturma*:

What would one do with a collection of a sculptures? Reduce it in scale in order to make it easier to store, or easier to compare, as with models of famous buildings from across the world? And if the sculptures are assembled together in one place, removed from their original sites, to what extent are they displaced and deprived of meaning? Do the sculptures make the site or the site the sculptures? (102)

And, more proactively, the retrospective book becoming a source of further ideas:

Models are provisional, a way of testing ideas, of suggesting what might be. Models which are never made refuse the viewer the possibility of actualisation, while offering him or her a wider range of possibilities. (103)

It occurs to me as I read this, thinking of an art finding its true retrospective in book form: A book, at its best, can return work to the state of the never-made. All three essays here are designed in different configurations, meaning nearly every page maintains a reciprocity of word and image, work and commentary. It's the images that are so powerful in this book, so auratic - and a long further essay could be written on how aura becomes a quality of these images. It's a tribute to the power of the books design and its contributers to articulate something of that aura, its qualities of atmosphere, spectacle, embodiment, technology, colour, and leisure. Or, as, once again, DGF's note puts it on the back cover, now with the whole book as what it comments upon:

*and books, cinecity, cosmodrome, exotourism, exodrome, park, promenade, solarium, tropicalization...

Susan Hiller, The Last Silent Movie (2007, video still).

Susan Hiller, The Last Silent Movie (2007, video still). I saw Susan Hiller's recent show at Matt's Gallery, and afterwards, like many people I guess, I had an argument with my friend about whether it was a film or not. If you haven't seen it, then the piece comprises thirty minutes of edited sound recordings from archives of extinct and endangered languages, including lists of words, field recordings, song and storytelling events, and stilted studio reconstructions of phrases and questions. The screen was blank throughout, with subtitles at the foot of the screen providing an English translation.

I saw the use of video and cinema as central to the pieces impact. Firstly, the cinema style presentation was appropriate to create a particular context of attention - the work was shown every half hour, with admittance only at the beginning, and seats in rows facing the screen. There was the curious presence of the blank screen, its own presence as a shape moving forwards or backwards, a definite but also uncertain and intangible presence that seemed appropriate to the languages we were listening to. Finally, Hiller has said that she wanted to take the recordings out of their archive-mausoleums and give them some life again. Even as it negated many of the normal components of the cinematic experience, Hiller's choice of medium admitted that it is as cinematic images that these languages are likely to acquire their greatest cultural currency.

Susan Hiller, The Last Silent Movie (2007, etching, plate 12).

My friend said all this was an example of how, if I liked something, I would say anything to try and persuade someone else how wonderful it was. For my friend, the centre of the piece was nothing to do with the form Hiller had found for presenting the recordings, and all to do with the recordings themselves. If anything, the filmic presentation distracted and a series of headphones on the wall that one could listen to would have been a more direct way of encountering the sound. But for me film was central to conveying the paradoxes at the centre of

Susan Hiller, The Last Silent Movie (2007, etching, plate 13)

In a recent Art Monthly talk at Tate Modern, Hiller talked of her interest in the anthropologist Benjamin Lee Whorf, for whom each language contains a particular concept of the world. She also talked of her Belshazaar's Feast(1983-84), in which video screens broadcast images of fire, responding to a newspaper story ridiculing an elderly woman who claimed to hear voices in the white noise coming from her television set after close-down. The piece seemed emblematic for Hiller of her relationship to extra-sensory or paranormal phenomena: avoiding debates on the reality or not of the voices, instead focusing on the woman's experience as an imaginative, culture-making activity.

Perhaps that is another reason why I found the evocation of cinema so key to

I'm interested in things that are outside or beneath recognition, whether that means cultural invisibility or has to do with the notion of what a person is. I see this as an archaeological investigation, uncovering something to make a different kind of sense of it. That involves setting up