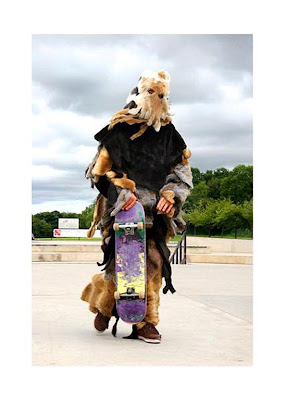

Juneau Projects, Sewn to the Sky (2007). Commissioned by Media Art Bath.

Juneau Projects, Sewn to the Sky (2007). Commissioned by Media Art Bath.DAVID BERRIDGE: There's a lot of cardboard in your work. Tell us about your relationship to cardboard. What kind of materials attract you?

JUNEAU PROJECTS: We used cardboard for this exhibition as a development of previous pieces where we made sculptures from machine cut plywood. We used this process as it allowed us to turn computer drawings into wooden folky-looking objects. For the show at Kingston we wanted to make something with a bit more energy and grunginess – so we used cardboard to create a more immediate handmade look.

Generally we are attracted to materials in terms of their inferred references and cultural resonances. They offer a short-hand language within the work.

DB: I found myself responding to your show on two levels. On the macro- scale there is the events you host and the broader categories such as music and nature and folklore. Then there was a more micro-level: the specific designs of the mugs, the musical instruments, or the stages. Are these two levels equally important? How do they relate?

Juneau Projects, (TOP:) The Principalities (2008), installation view, Stanley Picker Gallery; (MIDDLE:) The Principalities; (BOTTOM:) Traditional Grip (2007).

JP: The exhibition was intended as an installation which also functioned as a live venue. It could host events and bands but also had elements such as handicraft objects like the homemade beer mugs and painted tambourines with bottle-top jingles which exhibition goers could look at.

The macro and micro scales within the show is perhaps representative of our working process. We talk to each other about specific objects or images that we are interested in, often developing overlying themes for works and shows through these conversations. In this sense both levels have equal importance, feeding each other in the production of a piece.

DB: The stages, you say, are based on those at music festivals, while the show overall is called The Principalities. Is the music festival some sort of model or microcosm or utopia? And what kind of space do you hope to create in the gallery?

JP: We wanted the feeling in the gallery to be like being in a club or bar after hours – except when the events were on, when we wanted the feeling to be like being in club or bar… We liked the idea that the space would be 'activated' by events and the aftermath of the events would be evident in some way too.

The music festival was a starting point for thinking about how the show could be laid out and conceived. We made a piece of work last summer as part of the Art Trail at Big Chill Festival. We arrived before the festival opened and saw the stages and tents being installed. It felt like watching a series of Islands being created, different territories coming into existence. Much of our work straddles a number of different artistic fields: the principle of the music festival seemed to be an apposite solution for organising this.

.jpg)

Juneau Projects, (TOP:) The Principalities, photo: Ellie Laycock. (MIDDLE:) Sewn To The Sky (BELOW:) By The Paths Of The Flint Men

DB: Related to this, many of your cardboard designs evoke crests or emblems - all of which evoke some sense of clan or belonging. What kind of community are you asserting?

JP: We are interested in what role heraldry might have nowadays – how it loses its meaning and maybe gains a new meaning in a society that doesn't understand what virtues or qualities the animals or wavy lines represent. If we are making symbols for a new community, perhaps it is one built on a DIY approach to creative activity.

We have no strong desire to assert a model of community; we tend to use existing imagery to reflect overlooked or forgotten conventions.

DB: Your work spans music and art worlds. What are the differences in the cultures of each? What issues arise in working in both? What differences between the figures of artist and musician?

JP: We have been trying to address how music can fit into our artwork and vice versa by making our own sculptural instruments which we can play at live gigs and that will also act as artworks in a gallery. On the whole an art audience is probably more receptive to this – a music audience seems to think we have toy instruments or are pretending to play to a backing track.

We are not grounded in the music world. We have trained as artists and conceive our work as art work. We are artists exploring our interest and attraction to the music world.

Juneau Projects, Where I Lived And What I Lived For (2008).

DB: Would you rather be Matthew Barney or Bjork? What are the models and inspirations for your kind of music-art spanning practice?

JP: We would rather be Bjork's son to Goldie if she has one.

Christian Marclay's 'Guitar Drag' was a big piece for us when we started working together. We like Leonardo Da Vinci's silver horse skull lute and Ruskin's rock xylophone.

Most of our inspirations come from folk art or vernacular art where people have made objects for their own sake with no intention of exhibiting them.

.jpg)

Juneau Projects, (BOTH:) The Principalities. Photo: Ellie Laycock.

DB: How did you come to work together? Where did you begin and how has your work evolved?

JP: We were in a band together originally – which is where the use of music in our work comes from. We had made artwork at University which shared some common ground and we began to talk about ideas for projects which involved creating sound by putting walkmans in lakes or drilling cd players. At the beginning we didn't want to make objects so we mainly made live pieces and performances but we have come to terms with the fact that we enjoy painting and making objects which is central to our work now.

DB: How does nature figure in your work? Playing electric guitars in nature, guitars made of owls, a stage surrounded by cardboard trees. A nature-human hybrid. What's going on there? And what about the role of animals inparticular?

JP: Nature is a great source of emblems. We are attracted to the idea that society projects ideas about how we think we should live our lives onto the natural world. We seem to see ourselves as somehow outside nature or even against it in some way. At the same time images from nature are heroically over-used to the point where they become almost redundant, which is something that interests us as well.

Our main relationship with animals, beyond photographs and documentaries, is through pets, zoos and urban wildlife. The bird feeder becomes a restaurant for urban animals, a haven for the sparrow and squirrel. There's a joy to watching a pigeon eat a Quaver.

Juneau Projects, The Principalities.

DB: And the folklore elements. With Jeremy Deller at the Palais de Tokyo, your participation in Experimenta Folklore and so on, this is a current topic. But why is it relevant? How did your interest begin? Why is folklore engaging so many artists at the moment?

Juneau Projects, The Principalities.

JP: We are interested in stories as a way of generating imagery, which includes things like computer hacker folklore, biographical stories and literature as much as traditional folklore. For instance a recent piece entitled 'Acorn Archimedes' takes the form of a wall based water-jet cut wooden panel depicting two squirrels with a data cassette forming a kind of emblem.

.jpg)

Juneau Projects, The Principalities. Photo: Ellie Laycock.

We took cues for the imagery from a website which draws parallels between the rise of the Grey Squirrel in the UK and the subsequent demise of the indigenous Red Squirrel and the rise of Microsoft and the collapse of British based Acorn computers.

It's a bit chicken and egg maybe. Artists have always been interested in folklore and vernacular art. There is a spotlight shining upon that interest at the moment. This maybe leads to people being more interested in folk and also probably leads people to become sick of folk, which in turn will lead the spotlight to move somewhere else.

If anything perhaps folk is of relevance now in terms of its relevance to DIY culture. Skateboarding, with its self documentation and styling, is a good example of a folk DIY culture. Similarly the proliferation of affordable music recording technologies alongside the rise of promotional forums such as myspace allows for a new form of folk music to arise. This is equally applicable to digital art mediums such as video and photography.

DB: How strongly is what you create a critique of other kinds of culture? I'm wondering how you see the space you make as regards other art- or public spaces - alternative? eccentric? something else entirely...

JP: We both met working as technicians and invigilators at an art gallery and this experience made us sure about the kind of artist we didn't want to be.

We create spaces we are interested in seeing and using. We do not intentionally critique other art or public spaces, although this perhaps happens as a by-product.

Juneau Projects, Aggressive Localism (2007).

DB: Let's talk about the specifics of some of these objects. Your show at Stanley Picker contains a nice line in handmade mugs. Could you tell us about some of the specific designs and the process by which you come upon them?

Juneau Projects, Aggressive Localism.

Juneau Projects, Aggressive Localism.

JP: The mugs are made by covering existing coffee mugs with papier-mâché to form an absurd beer tankard shape. They are painted with crests and emblems which are a mixture of the cheveronels and wavy lines from heraldry which no-one understands and some natural imagery. One of the crests refers to the Westvleteren Brewery in Belgium, which produces what is often called the best beer in the world. It can't be bought from shops or other outlets, only from the monastery which houses the brewery.

We like the eccentricities of pub decor: the framed beer mat, the engraved pewter tankard, the jazzy chalkboard, the wooden spoon table number. The Principalities was in some way an indulgence for us, creating objects we might decorate a pub with.

.jpg)

Juneau Projects, The Principalities. Photo: Ellie Laycock.

DB: What kind of status do these objects have? Are you very careful about archiving/selling every cardboard cut-out, every mug, or are things more casual and disposable? Are there some things that are "works" and some things that are not? Is this important?

JP: It's a bit of a mixture – some pieces are made as stand-alone works and some as part of projects. Both methods produce some works which are made available for purchase through our gallery, fa projects. We have often made new or re-worked versions of pieces, particularly installation type works, and have re-configured and combined elements from past work. There is never a plan or catalogue of elements from an installation and if they are shown again they always change.

When works and objects are used by us as part of an installation they are there to serve the overall work primarily.

DB: I guess I'm thinking how difficult it is to keep things casual and improvised in an art world setting. One moment you're making hand-made objects from cardboard that are casual and home-made, the next you're Jorge Pardo. Or there's an "interactive environment" in a gallery space that no one is allowed to touch.

JP: We have always tried to make the works we want to make. The art world can be bewildering. We try and muddle our way through it, figuring it out as we go along. I think it is understandable that people's concerns change and shift. We find it useful to remind ourselves sometimes that this is our job, not necessarily our way of life.

DB: There was a schools workshop going on when I saw your show at Stanley Picker gallery. The teacher emphasized the hand made and lo-fi aspects of your work. Are those good categories for thinking about what you want to produce? Are you against more industrial systems of production, or artists commissioning others to construct their objects for them?

Juneau Projects, Trappenkamp (2008). Installation in the Sculpture Court at Tate Britain as part of Art Now (7 Jun-26 Oct 2008).

JP: Not at all. A number of the objects we produce are made through industrial processes. Our work Trappenkamp is a good example of this: the structure was designed by us in Google Sketch Up and built by a team of carpenters and the the panels were drawn out by us in Adobe Illustrator and cut out by a robot-controlled water jet.

One of the most fun parts of making art work for us though is the actual production side of things. We like making stuff. We enjoy looking at hand made objects. We have often had to employ lo-fi means to produce work, particularly earlier on in our career. We like to understand the processes we are using as it gives us a feeling of independence. Figuring out how to make or do something with the knowledge and skills you have can be a nice puzzle.

DB: The Stanley Picker installation is designed for events. But it is also open normal gallery times, sometimes for school groups, sometimes empty. What is the space when it is empty? How do you see the visitors experience of the empty space?

JP: The space when it is empty is still the space. It is as important to us when nothing is happening as when something is happening. If the space is unfulfilling to the visitor when there are no events on then we feel have failed somewhat in the creation of an interesting space. Our aim is to make an installation that does not need to be activated by performance but that is already active and can incorporate performances and events within it.

Juneau Projects, (TOP:) Noise machine (with Ed Bennett); (BELOW:) Where I lived and what I lived for.

DB: When you create an event - what are you aiming to do?

JP: We hope to create events that are entertaining. We hope to make events that explain some of the reasons we do what we do in a way that we cannot necessarily put into words. We like it that events are live and immediate and finite. We like it that only a few people might see them. We like it that people might be frustrated by the fact that they cannot see an event that has already happened in the space. At least it shows they're interested.

DB: Making such events central to your work evokes the participatory aspects of "relational aesthetics." Are that generation of artists - such as Pierre Huyghe and Rikrit Tiravanija - an inspiration for you or do you feel you are doing something different?

JP: Both of those artists are unavoidable. We've installed exhibitions by both of them and seen a lot of their work. Neither of us has read Relational Aesthetics. I think we're worried it might destroy the magic. It's also not available as a book on tape, our main reading format.

Juneau Projects, Where I Lived and What I Lived For.

DB: What are you working on right now? What key issues or subjects are you obsessed about at the moment?

JP: We've been thinking a lot about making little interactive video sculptures. We've also been trying to develop a new grunge aesthetic, or at least figure out what a grunge aesthetic might be.

We have recently started a blog called Compliment Sandwich which is also a platform for our new podcast called 'Compliment Sandwich'. We like podcasting, particularly the fact that there is a specific term, platform and audience for people talking into a machine.

We are enjoying remote control model boat makers. We like punk houses. We are interested in the possibilities of starting a 'night' as well as considering how we would live as the sole survivors in a post apocalyptic world.

+(Large).JPG)

+(Large).JPG)

+(Large).JPG)

+(Large).JPG)