Eamon O'Kane, Plans for the Past and the Future, installation at Plan9, Bristol, 9 Jan-15 Feb 2009.

Eamon O'Kane, Plans for the Past and the Future, installation at Plan9, Bristol, 9 Jan-15 Feb 2009. Two different projects have recently got underway - in London and Bristol - each, in its own way, trying to explore interrelated notions of art writing, criticality and community. First, the London based New Work Network and art-writing organisation Open Dialogues have collaborated on Critical Communities, in which two groups of artists-writers (in London and Leeds) explore these notions through a series of meetings culminating in a Print On Demand publication.

This week I'm also taking part in Free Press, a collaborative project organised by Trade Union at the Plan 9 gallery in Bristol. As part of this project Karen Di Franco and Sophie Mellor - who comprise Trade Union - posed the question: what critical models are currently available to artists-writers? The following is an unpacking and development of a post I originally presented as a contribution to the projects preliminary online discussion:

... This is a thinking-through of some books/magazines lying around here to try and get some ideas together about available critical models, starting from the art-writing part of the spectrum and magazines such as Dot Dot Dot, F.R.David, and The Happy Hypocrite where "each piece should be at once ABOUT and AN EMBODIMENT OF its subject, and together ought to congeal into some overarching theme" (DOT DOT DOT 17,4)

One of the characteristics of this is that there is less preoccupation with writing about particular art objects than with using the methods and approaches of certain kinds of art production to produce written texts (this also applies to Bookworks Semina series, whose call for proposals almost asks authors to absorb a diverse array of experimental art movements resulting in their own contemporary prose).

As might be expected from such an approach, original writing is one part of a strategy which also includes finding new spatial forms for existing texts, collaging, or transforming texts by placing them in new contexts...

We could also look at such examples as models of where criticism becomes an exhibition or event. Both Dot Dot Dot and Uovo made recent issues out of live events/ exhibitions/ or by turning the magazine's offices into a kind of open studio. As well as the specifics of such projects, they are useful in helping us think of critical as layered across different mediums, as a process of thought that has an unfolding trajectory through the forms of print, oral history, event, performance, internet...

The other advantage of this approach is that it is one way to think through the notion of criticism as project, which is perhaps the main insight that has emerged from doing this blog. In such a paradigm, the individual review or article acquires the status of the commodified, fetishistic object, and the project becomes a way of generating a more open economy, responsive to a broader field of both artistic and non-artistic cultural activity. That's the hope anyway.

This is one way I respond to the work of the Russian collective Chto Delat. Moving on from this I also extrapolate the position of writing that is multi-positional: before, after, during, other action. It is also here that we I begin to sense criticism becoming a pedagogical strategy.

However, I am also aware of the frameworks within which such activities are taking place and it's hard not to feel sometimes that Dot Dot Dot, F.R.David and The Happy Hypcocrite are performing a series of endless chess like manoevures within varying stylistic and institutional art world frameworks (in the latest issue of Dot Dot Dot they talk about how the magazine is now only financially viable through the obtaining art gallery residencies).

What models are there for thinking through this situation? Are there critical projects that break out of this, have different relationship to audience, derive their text from - or place it in - a different web of relationships...

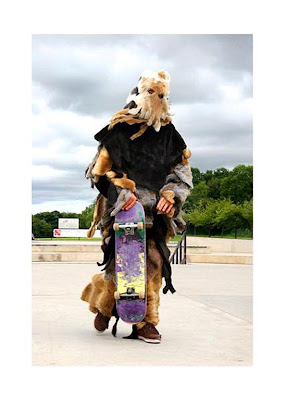

From TOP: Valerie Tevere and Angel Nevarez, Another Protest Song: Karaoke with a Message (2008); (BELOW:) The Center for Tactical Magic, Tactical Ice Cream Unit (TICU) (2008). Both commissioned as mobile projects for Democracy in America: The National Campaign.

I've been looking at Creative Time's A Guide to Democracy in America book (edited by Nathan Thompson) and, although still the product of an arts organisation, it does seem to be seeking for new networks within which its critical acts both take shape and are transmitted. Different parts of the project adopt models such as town meetings or community centres, seeing writing alongside the work of organising libraries, workshops, and community bookstores.

How can writing and teaching can become coterminous? How can we obtain more direct, literal relationships of writing and location, where criticality obtains through subject and focus: a writing documenting local industrial sites and projects, for example. Or a simple shifting between different communities in addition to that shifting between mediums: between different communities, nationalities, urban and rural, art-world and not: a whole series of nested scales.

I'm not sure I can think of writing and magazines which do this. But here are two examples of text which seem to provocatively relate to what I have presented here:

Emily Jacir's Who Said it? questionaire (in A Guide to Democracy in America) presents a lot of statements and asks readers to choose if they are by George Bush or John Kerry. This seems a great way to reveal and critically explore exactly what is at stake in language, and inculcate a process of thought and choice within the structure of a text.

I'm also struck by Paul Chans pornographic re-working of Gertrude Stein's Composition as Explanation for its combination of fidelity to and transforming of its source text by bringing to the surface or translating a particular quality of its own tensions...

I don't have any conclusions at this stage but maybe, looking at all this, the tension is between different ecologies: an institutional infrastructure of the art world, a broader network of cultural relations, and how a certain history of experimental art techniques and attitudes can navigate around and between both these categories.

*

More texts related to both these projects will be posted on More Milk Yvette as they unfold. Critical Communities also exists as an online forum, freely viewable, although only members of New Work Network can contribute. As an introduction to the Critical Communities project I posted the following short text:

When I started writing about experimental film several people said "oh its really important to have critical writing about new work." Which I enthusiastically agreed with, but I find this question more puzzling 18 months later, partly because the audience for any writing is so random and dispersed, and peoples needs (or not-needs) of such work so varied, that I'm not sure how this "important" actually works. Maybe it's better to be unimportant?

Do I feel I am making work accessible or creating an audience for this work? To a degree, yes, and to do stuff on the internet is, of course, to create some sort of international audience for writing about London events. Is it about responding to and for the artists themselves, or contribute to building some "artistic culture" in London? Sometimes I feel yes, whatever that means. I am presently trying to work with the randomness any critical act seems to have, as well as the notion of a blog almost as a character presenting its own cultural model.

I am increasingly practicing criticism as a kind of contextualising, which really overlaps with curating. Often I think of this as quite physically working with material - be it objects, words, ideas or jpegs, moving them around, finding new spaces and arrangements for them ( I think the journal F.R.David is a great example of this in terms of language).

I'm interested in how to do this "critical" not within an academic framework. So the historical models become New Journalism or Rolling Stone or Interview magazine or zines combined with a kind of scholarly research and detail and scope. Not sure these always go well together - in Amy Newman's oral history of Artforum (which is a gloriously bitchy self-presentation of one fractious critical community!) there's lots of raucous falling out over whether Clement Greenberg, French structuralism or Rolling Stone magazine is the way to go.

But I do like the idea of trying to write about things as if they are exciting cultural events - which they may well be - and doing so with exciting writing. Guess there's also the issue of whether exciting writing about boring events, or boring writing about exciting events, are ever good strategies...

Stewart Brand has a diagram about the different aspects of a society that function at different speeds (see below - it's also part of Hans Ulrich Obrist's Formulas for Now project), the idea being that a successful society works on all levels.

Intuitively, this resonates for me at the moment when I think about criticality- I've become interested in how to try and write about things as a way of recognising and creating a culture that operates on all six levels. Not sure what that means at all but it seems related to why am taking part in Critical Communities...

Also the creative-critical boundary, which maybe dissolves if you have this kind of broad based approach. But maybe it's not good for it to dissolve. Anyway-

+(Large).JPG)

.jpg)

.jpg)

+(Large).JPG)

+(Large).JPG)

+(Large).JPG)

.jpg)

.jpg)