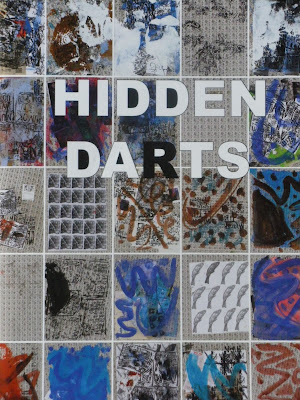

Josh Smith, Hidden Darts/ Hidden Darts Reader. Edited by Achim Horchdörfer. Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther König, Köln 2008. ISBN 978-3-86560-495-8

With recent exhibitions and catalogues of both Jess and Joseph Cornel, the figure of the artist as collagist has been acquiring a greater visibility. This may speak to a connection of such work and current preoccupations with, say, the re-enactment of historical events and the layering of fiction and reality in documentary. But, perhaps, it refers more strongly to a particular sense of the artist: as hoarder, arranger, and hermetic world-maker within what Jess' partner - the poet Robert Duncan - termed the "economy of the household."

I was thinking of some of these issues reading Hidden Darts and Hidden Darts Reader, the two-books in one that comprise the delightful bookwork accompanying New York artist Josh Smith's show at MUMOK, Vienna. Hold the book one way round, then the numbered verso pages intersperse a long interview between Smith and the Achim Hochdörfer - show curator and book editor - with texts by writers, artists and friends, who responded to Smiths instruction to describe "hidden darts" without mentioning either of the two words. Turn the book around and on the recto pages one has reproductions of the long sequence of around hundred paintings that comprised the MUMOK show.

In any act of reading the two, of course, cannot be kept separate. It may be a simple enough structure but it's one I didn't grasp fully until I was quite a way through the reader, which meant I'd paid careful attention to a lot of upside down images. All of which, I suspect, Smith would welcome, the catalogue being a more polished, commercial form of his photocopied, string bound artists' books, which, as Anthony Elms writes here, posit the book as "an opportunity to make another gesture, to push forward into new places by complicating the relationship to past works. Here, the book is not a backward looking catalogue, it is a confusing, boundless mess of questions." (8) Or perhaps, with its choreographed mix of ingredients, it is the book as show window:

Hopefully, what I produce could be compared to maybe a reflection in a store window; something that can be acknowledge and recognized, contemplated, processed, stored, and walked by, without a lot of effort and concentration. Also like a store window, because you pass it everyday and it puts a different thought into your head. Depending on your mood, the weather and what's behind the window, how dirty the window is...(58)

Actually, this book isn't a confusing mess at all. It has a clear concept, acted out on the level of both form and content. What's interesting is what it doesn't say. Indeed, for someone like me who hadn't encountered Smith's work before, it posits the book as a form of implied retrospective. The conversations, for example, are self-conscious, wide-ranging, witty, intelligent and intimate, so that one reaches the end of the book with a good sense of Smith's views, attitudes, and the way critics and curators understand his work. But although biographical facts, and details of his work emerge, there's no overall scene setting, no chronology, no development traced, no history of schools attended or galleries shown at, other than as it emerges almost incidentally and partially in conversation. Instead, there's a focus on what I first thought to call the moment, but is actually something different. Perhaps the conversation functions in the same way as Smith's discussion of his works: I put down the forms and then I see the emotions; I don't put the emotions in the form before I put them down. I write the story after the painting. I take these motifs of abstraction like lines, dots, squiggles and shapes of colors and zig zags and just layer them. The gestures could be anything and I am going to try to do it in the right way. These paintings just have as much emotion as an expressionist painting, except they were made in reverse... I am trying to make a point that emotion can come from other places besides internal emotion. (90-91) Smith's dialogue with Hochdörfer is broken into seven chapters, which offer a useful taxonomy of the key concerns Smiths practice, understood broadly, raises, and one which I think has a certain suggestiveness even as a simple list: Oral History, Hidden Darts, Pop Expressionism, Artist's Community, Working Ethos, Cancelled Television Show, Appropriation and Dedication. If expressionism is one artistic strategy Smith's work an evoke, then the other is appropriation. Here, again, Smith stresses his differences: I don't like stuff that takes rather than gives. In my way of working I try to establish a sort of acceptance of the limitations of art. In this respect I am definitely not an appropriation artist. I am referring to a lot of artists and ideas because it helps to show the process of filtration that my work goes through. I am very judgmental and quick. I always have a plan but I don't expect the plan to work. (81) As for the contributions by others that break up the interview, they are a varied bunch. Many, whilst enjoyable, I felt functioned primarily as communiques within the context of the authors friendship with Smith. Only a few sought to open up into a broader critical debate. I was most drawn to the formal inventiveness of Kerstin Brätsch's list poem, and to Amy Silliman's short essay "On Embarrassment." The later comprises a fable about visiting the studio of "someone very sophisticated and up-to-date." You look at many "trophy paintings" before the artist "sheepishly" shows you a painting that has been turned to the wall: ... and it's an ugly brown one with an embarrassing image on it, and it turns out to be the one you like the most. And when you tell the painter this, he or she brightens up because you have given an embarrassing and off-limits painting the permission it needed to live. But really, it IS the best painting in the room because it's the one where you feel the strangest edge, the most out-there and unafraid quality, the painting that goes to a really weird bad place without the baggage of shame or guilt. This is not a painting for everyone mind you. This painting is perverse, and in being so, it expresses aggression. Well, that's how I've come to like and think of a certain kind of expressionism. Of course this could merely put embarrassment in a kitsch category of so-bad-it's-good - which is something Josh is constantly playing with. But this is more than a strategy of kitsch: it is an awareness of history, in a way, because it is a double negative position, a position from which a certain kind of critical theory has already been absorbed and the artist is trying to go further, to make an object or have an attitude or find a place to stand that has not been sanctioned by art bureaucrats. This is the cliff edge one feels around for. Embarrassment is therefore a sign that one is at risk of exposing one's feelings, which is a good thing, especially if these feelings are ugly and contradictory. I look for these complications in Josh's paintings. He has built an infrastructure that is shored up with analysis and calculation, but nevertheless it leaks out the back with painterly desire and instinct. And it is for this reason that I care about his work so much. I don't like any work that isn't equally one thing as another: as revealing as it is concealing; as cold as it is heartfelt, as hating as it is loving. (38-9) I copied all that out because it seems to delineate aspects underpinning a large number of shows, events, and writings I've encountered lately. Then turn the book over and look through the sequence of images. Each begins as a 5x4 feet canvas. Each is covered in what looks a sheet of hand drawn stamps advertising the Lyon Biennale. Both in itself and in relationship to the other canvasses, then, each piece already propounds a serialism, and this is compounded by what Smith paints or collages on top. Some of his repeated strategies include: large, flat areas of color; bold distinctive lines - curving, zig-zags and spots; hand painted words, sometimes announcements for other art shows. Whole sheets of newspaper, menu's, or what looks like sheets from Smith's sketchbook are also added, and these may then also be overlaid with lines or masses of color. Smith observes that he can work on as many as 100 paintings simultaneously. The book's cover reproduces them all, in a grid, echoing the pattern of stamps from which each individual canvas begins. It highlights the tension of similarity and difference, between a certain improvisational casualness and the defining parameters of canvas and series. Inspired by this book, I sought out some other examples of Josh Smith's work, in other books and on the internet. Nothing else prompted the strong response I had to the work in Hidden Darts - even when, as in Smith's own website - it presented some of the same images, testimony to this books success in finding a form for the presentation and discussion of his work.