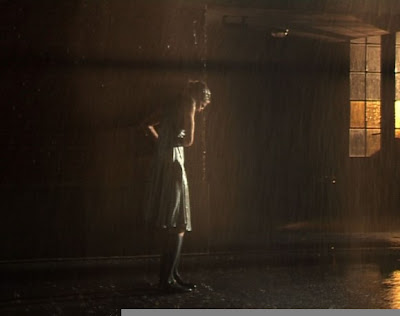

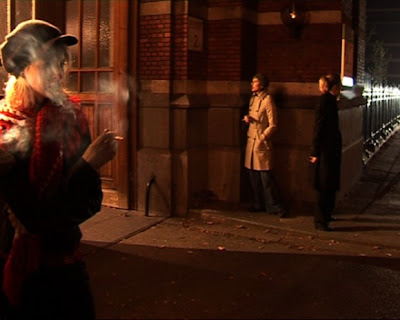

Top: Chantal Akerman, To Walk Next to One's Shoelaces in an Empty Fridge (2004). Middle and bottom: Women from Antwerp in November (Femmes d'Anvers en Novembre) ( 2007). All images copyright the artist. Courtesy Marian Goodman Gallery, New York/Paris.

Top: Chantal Akerman, To Walk Next to One's Shoelaces in an Empty Fridge (2004). Middle and bottom: Women from Antwerp in November (Femmes d'Anvers en Novembre) ( 2007). All images copyright the artist. Courtesy Marian Goodman Gallery, New York/Paris.

What do we learn from the Chantal Akerman show at the Camden Arts Centre? First, this is an artist who wants to explore the image in space, where it becomes multiple, both in its own patterns of projection and through the movements of its audience. Second, this is an artist for whom the film image is always entwined, overlaid, is itself language. Thirdly, this is an artist acutely aware of film style and its consequences, making decisions about form and media, fully aware of how each constructs self-hood and society in unique ways.

The first part of To Walk Next to One's Shoelaces in an Empty Fridge (2004) comprises a large gallery-filling spiral tulle. On the tulle are projected lines of text, accompanied by quiet, classical music. I couldn't read much of the French text or identify the music, but the piece is a meditative experience, through which the viewer can wander, choosing their position in regards to shifting tides of words, with both sides of the tulle screens, lights and shadows, having equal value. A translation would have been useful, although the work has its own phenomenological completeness without it. It's also usefully viewed holding in mind Edna Moshenson's summary:

It is a cinematic autobiography of sorts, which contains her thoughts about cinema and the power of the cinematic image; about the Second Commandment that forbids that making of graven images; about her work and about what has nourished and motivated her. Other parts of the text touch upon her family biography - her relations with her mother and the experience of growing up and living in the shadow of trauma, silence, nightmares, and invented memories. (Chantal Akerman, A Spiral Autobiography, 16)

The second part of To Walk comprises another tulle screen hanging in the middle of the gallery, and on which are projected pages of handwriting and a portrait from an old notebook. On the wall of the space a black and white double screen film documents Akerman and her mother discussing Chantal's upbringing, her mother's experience of the concentration camps, and, principally, the notebook, which belonged to Chantal's grandmother, who died in the camps. Depending on where you stand to view, the notebook on the tulle can be visible or absent, foreground or background, but it is always part of the experience.

Ackerman asks her mother to read from the notebook. The film documents her struggles, both to make sense of the handwriting and to remember her Polish reading skills. The notebook begins "I am a woman! That is why I cannot speak all my desires and thoughts out loud..." - and Akerman has to point out the message to her mother, making sure its presence becomes acknowledged. Even here, amongst intimacy, family and friendship, possibilities of silence and mis-representation are always present. Such histories are also tied to Akerman's development as a film-maker, informing her mothers conviction she should follow her passions, whilst her father was more cautious. Chantal observes that only in her first film - the short Blow Up My Town (1968) - has she ever been able to combine the tragic and the comic that defines her families experiences.

Both images: Women from Antwerp in November (Femmes d'Anvers en Novembre) (2007). Copyright the artist. Courtesy Marian Goodman gallery, New York/Paris.

Femmes d'Anvers en Novembre (Women from Antwerp in November) (2007), the show's final piece, is where we see Ackerman's awareness of style and film genre most at work. On one side of the gallery is a five screen production of young women smoking. The shots and the women differ but they are all heavily stylised in a way evocative of film noir and advertisements. Women smoke whilst on the phone, alone in moodily lit alleyways, in black and white, in the rain. There are other images which disrupt this a little bit - notably one of the women gathered around a table - but they too become part of this analysis of a social act - one made popular through its visual stylisation, not least in the history of cinema, which is here also linked to certain categorizations of femininity. The installation recalls Akerman's 1979 comment on her work:

I try to make a very distilled cinema where there are no images that are, let's say, sensational. For example, instead of showing a 'public' event because it is sensational... I will tell the story of something small nearby.

Here that "distilled cinema" means taking on directly a particular form of cinematic representation, inhabiting it, beginning to subjectivise it. As well as smoking's now problematic status, this is explored through a second screen in which one of the women is filmed in what looks like HD video close up: the camera lingering over mouth, lips and face as she smokes a cigarette. Still stylised, of course, but not so it can be designated as glamorous according to the codes of film noir. It is not possible to watch both screens at once, the end result being a piece and viewing experience that proposes a contemporary subjectivity combining spectacle, film style, femininity, sense of self, private and public modes of being.

The show also includes Akerman's 1972 film Hotel Monterey. Over 65 silent minutes, Hotel Monterey is constructed as a series of spaces - corridors, rooms, beds, lifts, doorways - that in long, meticulously framed shots become negotiations between spaces, light, movement and the people that sometimes come into them. Camera movements comprise slow pans along rooftop railings or a long, slow zoom up and back along a corridor to a whited out, over exposed window. The film stock suggests a building being subsumed in a psychologically charged heaviness of murky greens, browns, blue and yellows. Outside shots are are always related to the inside: skylines are outer manifestations of a buildings heating and water systems.

Documentation and abstraction, neutral observation and obsession, the new and the haunted, the framed and random, time changing, time frozen. Here is Akermans film career beginning, bearing testimony to the alien and familiar experience of America, and also the cinema of Mekas, Warhol and Snow she encountered there. In making work for galleries, Akerman often re-works or combines films to create multi-screen installations. Here the act of looping a film with no credits or title sequences is all that is required to link the films temporality to the patterns of memory, history, trauma and representation that the show's more recent pieces explore, perhaps more consciously.

What do we learn from Akerman's exhibition at the Camden Arts Centre? I started with this question because each of the pieces here approach a specific problem, seeking to learn something about it, at the same time as recognizing what they want to learn, its connection to history and trauma, is perhaps unknowable, only revealable in traces of "something small nearby" to which Akerman is so attuned. The artists only approximation of certainty is in the works form. Often, too, there is the hope that the image itself could be a form of writing. In a world dominated by availability of cinematic images, the written language in these pieces proposes a system of representation that requires debate, translation, embodiment, relationship, distance and layering to begin to, tentatively and hopefully, become legible.